Ce travail n’est qu’un exposé des éléments devant amener à considérer la prise en charge du Covid au travers de la « voie histaminique ». Il est certainement empreint d’une certaine subjectivité mais, comment pourrait-il en être autrement face au constat pour un praticien de terrain de la lenteur du déploiement des traitements curatifs potentiels, les polémiques, interdictions et menaces.

Le lecteur avisé saura écarter l’effet d’usure de cette situation éthiquement et intellectuellement inadmissible pour ne retenir que ce qui, ici, est primordial : l’ouverture (enfin) d’un axe de réflexion thérapeutique et de recherche.

Certaines approches sont très théorisées, il ne s’agit là, non pas de démonstrations mais uniquement de l’évocation d’axe de réflexion. Juin 2021

Résumé

Fin février 2020, à l’émergence européenne de ce qui était encore une épidémie liée au SARS-Cov2, nous avons, sur la base des données épidémiologiques, cliniques, paracliniques et évolutives du CoviD-19, formulé l’hypothèse d’une pathogénicité du SARS-Cov2 médiée principalement par la combinaison virus-hôte et ce dès le contact initial.

De l’interaction avec l’agent pathogène, le système immuno-inflammatoire de l’hôte produirait une réaction, parfois exacerbée et délétère à court, moyen voire long terme.

Le SARS-Cov2 possèderait un pouvoir de contagiosité élevé mais surtout une capacité (sans aucun doute encore jamais rencontrée ou appréhendée) à provoquer chez son hôte des réactions excessives du système immuno-inflammatoire ce dernier, supportant vraisemblablement toute ou partie de la pathogénie.

La plus ou moins grande susceptibilité réactive du système immuno-inflammatoire de l’hôte en réponse à son contact avec le SARS-Cov2 déterminerait dès lors l’évolution clinique et in fine la gravité de la maladie (immédiate ou différée (Covid-long)).

Cette susceptibilité de l’hôte à produire une réaction initiale de défense, se « retournant » plus ou moins rapidement contre lui et de façon plus ou moins forte, pourrait ainsi expliquer les différentes hétérogénéités du Covid-19 tant cliniques, que biologiques ou évolutives et ce, quel que soit le stade de la cascade immuno-inflammatoire et/ou le moment évolutif.

De même, et en droite ligne, les effets délétères en lien avec ces activations du système immuno-inflammatoire sont potentiellement inquiétants pour les « séquelles » qu’ils pourraient laisser ou les réactivations lors d’un second contact.

Dès lors, c’est à une dangerosité potentielle non pas de l’agent viral (SARS-Cov2) de façon intrinsèque mais bien dans la réaction suscitée chez l’hôte, à laquelle les malades seraient soumis.

La réactivité intrinsèque propre à chaque individu déterminant en quelque sorte « son » Covid19 en termes de cinétique évolutive, de clinique mais aussi de gravité voire de séquelles ultérieures.

D’une manière ou d’une autre, le SARS-Cov2 génèrerait une réaction immuno-inflammatoire pouvant s’auto-emballer de façon progressive ou/et explosive voire infraclinique.

Ce caractère parfois explosif et imprévisible ainsi que les hétérogénéités observées et les fonctions connues de l’histamine orientent vers la mise en jeu de cette amine biogène lors de l’initiation mais aussi au décours de l’activation et l’emballement du système immuno-inflammatoire voire peut-être de façon directement viro-induite.

Différentes observations cliniques sont venues consolider la possible pertinence de notre hypothèse. De même, les progrès des connaissances dans le Covid-19 ont apporté de nombreux éléments confortant l’implication possible de l’histamine et avec elle, l’intérêt probable des antihistaminiques.

Nous reprenons ici l’ensemble de ces éléments en complétant nos écrits antérieurs (février-mars, juin 2020) -cf annexes - à la lumière de nouvelles recherches bibliographiques et des nouvelles connaissances (juin 2021).

Contexte et hypothèse initiale

Dès l’émergence des premiers cas en France de Covid-19 nous avons formulé une hypothèse quant à la pathogénie liée au Covid-19.

La participation du système immuno-inflammatoire serait à l’origine, au travers de l’interaction agent pathogène-hôte, de la symptomatologie hétérogène observée et de la gravité variable à la fois inter et intra-individuelle et ce, dès les premières interactions agent pathogène-hôte.

Ainsi, la physiopathologie inhérente au Covid-19 serait issue des effets délétères principalement -voire exclusivement- en lien avec une réaction excessive du système auto-inflammatoire et auto-immun de l’hôte. La caractéristique même du système immuno-inflammatoire en termes de « puissance de réponse » pouvant apporter compréhension quant aux observations de l’hétérogénéité qui semblait être de mise dans le Covid-19.

Le virus SARS-Cov2, pour contagieux qu’il soit, apparaît, en lui-même, dangereux quasi uniquement dans sa capacité de déclenchement d’une réaction inflammatoire et immunitaire qui peut devenir excessive et délétère à court, moyen voire long terme.

Dans ce concept, les effets physio pathogéniques « indirects » liés au SARS-Cov2 seraient responsables de la maladie. Ils seraient également présents dès les stades précoces et « fusionnés » avec les effets physio pathogéniques « directs » du SARS-Cov2. Ainsi, dans le Covid-19, les effets délétères viraux ne seraient pas suivis, comme il n’est pas inhabituel de le voir dans certaines viroses après une phase évolutive plus ou moins longue, d’effets indirects mais provoqueraient d’emblée la mise en jeu de la chaine de réactions délétères « indirectes ».

Dans cette hypothèse, les effets physio pathogéniques « indirects » liés au SARS-Cov2 seraient impliqués (donc à cibler sur le plan thérapeutique) dès leur genèse (et donc peut-être dès le contact initial hôte-virus). Ce ciblage précoce peut permettre de limiter les effets délétères dont le possible emballement immuno-inflammatoire (bruyant ou non).

De cette notion, la charge virale lors du contage pourrait devenir moins déterminante en termes de capacité du SARS-Cov2 à induire le Covid-19. En effet, dès lors que ce serait les effets physiopathologiques « indirects » qui entreraient en action via l’interaction virus-hôte, la charge virale initiale bien que potentialisant le démarrage voire l’emballement, deviendrait moins déterminante en termes de capacité d’induction de la maladie (et donc également en termes de contagiosité). Ceci peut être approché avec les concepts en vigueur en allergologie et selon lesquels, la charge d’allergène, pour cruciale qu’elle soit, n’est pas quantitativement limitative au déclenchement de la réaction pathologique.

Ce dernier concept pouvant peut-être, selon nous, rendre compte des différentes observations épidémiologiques et cliniques très hétérogènes. La sensibilité individuelle, la « réactivité » intrinsèque, est, en effet, d’une « puissance » variable et propre à chaque individu. Le SARS-Cov2 pourrait dès lors provoquer des réactions individuelles très variables en contact primaire mais aussi secondaire. Pour compréhension nous ferons cette analogie : une sorte de fonction d’agent à comportement « allergène universel » (pour le comportement « inducteur »).

Les perspectives d’un tel comportement hypothétique dans l’interaction hôte-virus généreraient de facto des implications dans l’élaboration d’un vaccin et/ou dans l’obtention d’une immunité protectrice. Dans cette hypothèse, il y aurait sans doute un pouvoir « d’arrêt » viral mais peu ou pas d’action sur la « maladie » Covid-19 avec cependant certainement neutralisation de certains effets physiopathologiques renforçant encore, lors de contages ultérieurs, l’hétérogénéité clinique déjà observée pouvant amener à des formes cliniques « abâtardies » ou non typiques voire éventuellement des formes encore plus « explosives ».

Dès lors, le cadre nosologique du Covid-19 serait largement hétérogène aux regards des spécificités individuelles (voire intra-individuelles) de réponse et mise en jeu du système immuno-inflammatoire et, notamment, en ce qui concerne la symptomatologie initiale.

Cette caractéristique semblait dès lors pouvoir rendre compte de l’hétérogénéité épidémiologie et clinique constatée.

Les données biologiques à notre disposition ensuite faisant état « d’orage cytokinique », plaidaient également pour une participation auto-inflammatoire et auto-immune dans les formes graves de la maladie au-delà des comorbidités. L’évolution en deux phases avec aggravation à J7-J10 rentrait également totalement dans cette mise en jeu réactionnelle et in fine, délétère, du système immuno-inflammatoire de l’hôte.

Sur ces bases, il convenait donc de moduler au plus vite cette réactivité anormalement élevée du système auto-inflammatoire constatée et ce, particulièrement chez certains patients dont la prédisposition à réagir est forte et reste à comprendre.

Le ciblage et l’utilisation d’une molécule à effet uniquement virucide ou/et virostatique, bien que logique, ne semblait cependant pas permettre de s’opposer à la cinétique de mise en route de la réaction auto-inflammatoire et auto-immune, ni pouvoir stopper sa mise en jeu et au final, la maladie.

De cette hypothèse physio pathogénique initiale, l’utilisation de certaines classes thérapeutiques apparaissait évidente pour leurs actions et rôles connus dans le système immuno-inflammatoire : antihistaminiques en premier lieu (en particulier anti-H1), anti leucotriènes, antipaludéens de synthèse et immuno-dépressiogènes ou immuno-bloqueurs.

Compte-tenu de son caractère ubiquitaire au sein de l’organisme, de sa mise en jeu précoce dans ses actions cellulaires et cliniques connues, l’histamine nous apparaissait être la molécule dont le ciblage devait être prioritaire.

Sa mise en jeu pouvant du reste, relever d’une activation initiale mais aussi lors de l’évolution de la cascade immuno-inflammatoire avec de plus, au-delà d’une induction augmentée, une possible diminution (associée ou non à l’induction) des capacités de l’organisme des malades, d’élimination-neutralisation.

En d’autres termes, implication possible de l’histamine par excès de libération et/ou production associée(s) ou non à une baisse des capacités de clearance « physiques » voire « fonctionnelles », le tout, induit par l’interaction hôte-virus initiale (et ultérieure).

Les antihistaminiques bénéficiant d’un recul et d’une simplicité d’utilisation, cette simplicité d’utilisation en faisait de plus, des candidats plus que concrets et rapidement exploitables dans leurs potentiels effets dans le Covid-19 tels qu’avancés dans sa physio pathogénicité (système immuno-inflammatoire). Début mars 2020, la recherche documentaire effectuée ne montrait aucun article sur le sujet (Histamine - antihistaminiques – Covid-19).

Les autres classes thérapeutiques possiblement utiles, intervenant à des temps différents et ultérieurs, ne comportaient pas le potentiel « d’arrêt » des antihistaminiques selon notre théorisation, mais restaient en possible utilisation séquentielle complémentaire.

La prise en charge thérapeutique du Covid-19 nous semblant dès lors pourvoir relever d’une « thérapie multi-classes à déploiement séquentiel » avec en point de départ (et continu) les antihistaminiques.

A chaque phase de la maladie une réponse thérapeutique dédiée en suivant les évènements et éléments de la cascade immuno-inflammatoire en action, avec de près ou de loin les effets initiaux (« promoteurs ») ou d’entretien et/ou renfort de l’histamine, la charge virale et/ou les nouvelles contaminations prenant également une importance renforçatrice possible.

Dans cette hypothèse, il s’avère par ailleurs que la réalisation d’essais cliniques pouvait de facto se voir rendue plus difficilement reproductibles en raison de ce possible biais « de phase » dans les populations étudiées, compliquant encore les éventuelles approches thérapeutiques.

Par la suite, nos différentes observations cliniques semblaient montrer (de façon subjective) un effet rapide des antihistaminiques (antiH1) sur une grande partie de la symptomatologie initiale observée lors de la déclaration d’un Covid 19 ainsi qu’un raccourcissement notable de sa durée. Nous avons alors communiqué ce constat en attirant l’attention sur l’utilisation la plus précoce possible des antiH1 dans le Covid-19 (sans attendre le déclenchement de formes graves : au plus tôt de l’apparition du Covid-19) dans l’espoir de voir se mettre en place des études de bonnes factures scientifiques 1.

Nous avons dans le même temps formalisé nos observations et établi un recueil de données observationnelles basées sur l’utilisation d’un médicament (rappelons-le en vente libre en France et dans de nombreux pays), en dehors de son Autorisation de Mise sur le Marché (AMM), comme du reste tous les médicaments utilisés à ce jour dans le Covid-19, en commençant par le paracétamol. La prescription, hors AMM étant parfaitement autorisée et encadrée par la législation française 2.

Dans ce contexte, nous avons donc mis en forme nos résultats, issus d’un mixte entre recueil observationnel et utilisation hors AMM, afin de rendre nos observations et propositions communicables. La place précise de ce type d’écrit ne nous semble in fine pas prévue dans les classifications. La pratique médicale de prescription hors AMM, autorisée et encadrée selon les termes du Code de la Santé publique n’étant évidemment pas usuelle en termes d’analyse d’efficacité thérapeutique mais, en période pandémique, les résultats observés se devaient de bénéficier d’une « remontée de terrain » en calquant au mieux aux exigences démonstratives.

Évidemment, aucune randomisation initiale n’a été mise en place, la mise en forme des données et résultats ne relevant pas d’une volonté initiale d’étude mais d’un constat de terrain calquant à notre théorisation initiale.

Bien que conscients des faiblesses tant en terme méthodologique que statistique, nous avions fait le choix d’une diffusion le plus large possible afin de sensibiliser le plus d’équipes possibles au sujet, avec cette fois, plus de « matière » que lors de notre communication initiale. Le contexte pandémique et la réaction à mettre en place relevaient (et relèvent encore) de défis non égalés dans le passé ; il faut ainsi parfois des approches différentes pour lancer les approches classiques. Le recueil de données de prescription hors AMM en a été, selon nous, à l’évidence l’une d’elle.

Au-delà de la méthodologie, résultats et concept se devaient en effet de se voir traités et explorés à leurs justes potentiels entrevus.

Covid-19, histamine, antihistaminiques : apports récents et hypothèse initiale

Les travaux et propositions réalisés dans la lutte contre le Covid-19 sont multiples et d’une densité et rapidité sans précédent.

Nombre d’entre eux ont apporté des précisions qui nous semblent pouvoir permettre d’avancer dans l’approche et compréhension des possibles liens entre SARS-Cov2, Covid-19, histamine et antihistaminiques, c’était le cas en juin 2020 lors de notre première mise à jour, c’est encore plus le cas un an après…

Comme indiqué dès février 2020, nous estimons que le Covid-19 relève de l’interaction virus-hôte au travers des différentes réactivités individuelles en lien avec l’histamine. La précocité d’interagir avec le système histaminique avait été soulignée comme primordiale. Ce faisant, l’histamine revêt des potentiels délétères directs mais aussi indirects (activation mastocytaire, production de cytokines…). Afin d’englober ces deux types d’effets, nous parlerons ici de « système histaminique » englobant donc l’histamine et les « effets secondaires » liés à l’histamine (activation mastocytaire, production de cytokines…).

Il est donc réalisé ici un rapide point quant aux travaux faisant état des relations entre Covid-19, « système histaminique », antihistaminiques directs, actifs sur les récepteurs à l’histamine (dont il existe 4 types) et « antihistaminiques indirects » c’est-à-dire, tous éléments s’opposant aux effets de l’histamine.

Propriétés antérieurement connues de l’histamine et des antihistaminiques

Au-delà d’une seule théorisation du rôle possible de l’histamine (et ses implications biologiques) dans le Covid-19, notre réflexion quant au positionnement des antihistaminiques dans la prise en charge thérapeutique de Covid-19 se basait sur certaines propriétés antérieurement connues.

Afin de mieux appréhender le potentiel intérêt de la lutte contre l’histamine et ses effets dans le Covid-19, nous ferons un bref rappel.

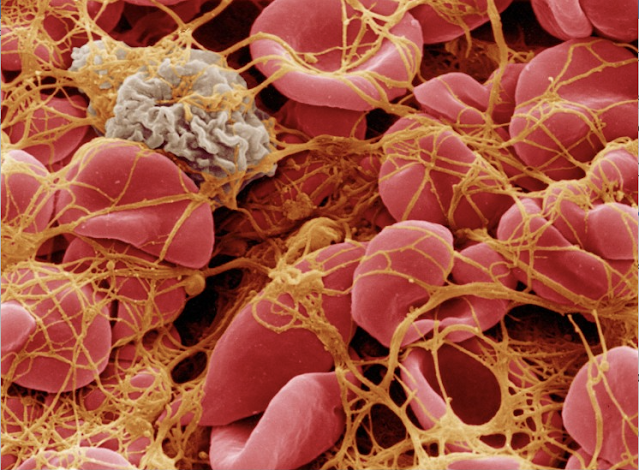

L’histamine est libérée par différents type cellulaires et notamment par les mastocytes et les basophiles avec une action médiée par différents types de récepteurs 3. Elle intervient dans la réponse immunitaire avec une action de modulation de la différenciation des lymphocytes T helper (Th) en Th1 – Th 24.

Pour mémoire, les Th1 activent les macrophages et l’immunité cellulaire et les Th2 activent la production de lymphocytes B 5. Les cellules B et T interagissent ensuite au niveau des aires lymphoïdes secondaires et la production de la réponse humorale spécifique de l’antigène concerné, débute. Les IgE vont alors activer les cellules mastocytaires causant leur dégranulation et la libération d’histamine6.

Les liens entre histamine et IL1, IL6..etc…sont connus de longue date.

L’histamine est également impliquée dans la réponse à certaines infections virales avec une capacité de libération d’histamine lors d’une infection virale comme cela a, du reste, été bien démontré chez l’animal pour certains virus 7.

Au titre des réponses aux infections virales, il a été montré que les antagonistes RH1 de l’histamine avaient un potentiel inhibiteur sur l’entrée de certains virus, dont les virus Ebola et Marburg 8, mais aussi les virus influenzae 9.

Cette potentielle capacité inhibitrice est donc primordiale à considérer avec le SARS-Cov2 et, de multiples études sur lesquelles nous reviendrons, ont permis d’établir de nombreuses pistes sur le potentiel inhibiteur des antihistaminiques.

Il est connu que l’histamine induit la libération de certaines interleukines par différents type cellulaires dont notamment les cellules endothéliales 10 dont l’implication possible dans les processus lésionnels du Covid fera l’objet d’un point spécifique ci-après.

De même, il est utile de mentionner l’implication de l’histamine comme potentialisateur d’autres monoamines avec au final une action pro thrombotique connue 11 (agrégation plaquettaire)12.

Au titre du caractère de lutte contre les processus thrombotiques, certains antihistaminiques antiRH1 sont connus comme pouvant s’opposer au PAF (Platelet Activating Factor) avec un attrait tout particulier dans leur éventuel repositionnement dans le Covid-19 afin de lutter contre les micro-thromboses induites dans cette maladie 13.

Il existe bien d’autres implications et conséquences (directes ou indirectes) de l’histamine dans la réponse immuno-inflammatoire.

Nous n’avons fait mention ici que des implications connues utiles à la pleine compréhension du reste de notre exposé.

SARS-Cov2/Covi-19 – Syndrome d’activation mastocytaire

Le SARS-Cov2 interagirait sur les mastocytes et les activerait 14. Ainsi, le SARS-Cov2 aurait la capacité de provoquer la libération par les mastocytes de différents médiateurs dont le TNFα, des prostaglandines, l’IL1, l’IL6, des leucotriènes et de l’histamine 15.

L’activation des cellules mastocytaires a été mis en évidence dans le Covid-19 par différents travaux 16,17,18,19,20,21 et semble ainsi bien ancré dans la pathogénie globale du Covid-19, confortant notre hypothèse initiale quant au lien entre Covid-19 et "système histaminique ».

Cette notion d’activation des cellules mastocytaires dans le Covid-19 ouvre donc un champ d’intérêt sur les molécules connues ayant une action stabilisatrice des mastocytes dont les antihistaminiques 18,19,20,21.

SARS-Cov2/Covi-19 – histamine : constats anatomo-pathologiques, IL1, IL6 et autres

Il a été rapporté que les atteintes de différents organes dans le Covid-19 pouvaient être mises en relation avec le constat d’endothélites notamment en lien avec une activation endothéliale liée à l’orage cytokinique observé au décours du Covid-19 (rôle pathogène viral direct possible également) 22.

Soulignons que l’atteinte cellulaire principale observée était l’apoptose 22. Ceci correspond à la cytotoxicité connue in vitro de l’histamine 23.

Ainsi, sans pour autant en donner lien de causalité et bien que l’extrapolation in vivo d’une action pro ou anti-apoptotique de l’histamine sur ces types cellulaires n’est pas ici documentée, une possible action cytotoxique de l’histamine, après présence prolongée et/ou à des taux élevés, resterait compatible avec les observations faites.

Par ailleurs, l’inflammation de l’endothélium, connue pro-thrombotique pourrait être le résultat d’une réaction immuno-inflammatoire lors du Covid-19 entrainant entre autres, une dysfonction endothéliale multi-viscérale.

Les atteintes microvasculaires et thrombotiques ont, du reste, été assez rapidement décrites lors du Covid-19 24. Comme précédemment mentionné, l’implication de l’histamine comme potentialisateur d’autres monoamines avec au final une action pro thrombotique connue 11,12 (agrégation plaquettaire), ces constats d’atteintes microvasculaires et thrombotiques ne font donc que renforcer la nécessité de mieux appréhender la mise en jeu du « système histaminique » (avec ses liens par ailleurs connus sur d’autres pro coagulants) dans la genèse de ces anomalies lors du Covid-19.

Soulignons qu’il s’agirait là d’une action de plus, renforçatrice du potentiel pro coagulant de la dysfonction endothéliale induite par la « seule » endothéliite.

Les antihistaminiques pourraient peut-être, contribuer à la limitation de ces phénomènes micro-thombotiques (voire en supprimer la genèse et/ou « l’amplification ») comme également évoqué par des hypothèses similaires plus récentes13.

Par ailleurs, si l’on considère l’expression cellulaire des récepteurs antihistaminiques, en particulier RH1, il s’avère que les cellules endothéliales semblent exprimer fortement ce récepteur 25, sans que cela ne préjuge de l’action induite par l’histamine.

Il est démontré que les cellules endothéliales (artère coronaire humaine) voient accroitre la production de certaines cytokines (IL6, IL8) en présence d’histamine avec une relation dose-dépendante et une sur expression en présence notamment de TNFα. Cet effet de l’histamine sur la production de cytokines étant bloqué par l’antagonisation des récepteurs RH1 (par la diphenhydramine) et pas par celle des récepteurs RH2 10,23.

Il apparaît dès lors possible d’envisager que, suite à l’activation par le SARS-Cov2 notamment des mastocytes, Il se produise une libération d’histamine. L’histamine induirait ensuite, notamment sur les cellules endothéliales de proximité, une accentuation de la production de cytokines et en particulier d’IL6 (ce d’autant que les mastocytes sont connus pour libérés après activation également du TNFα14 qui augmentera donc le potentiel inducteur de l’histamine).

Il apparaît également qu’il existerait une différence de cinétique dans la production de ces différents médiateurs, avec, en ce qui concerne l’histamine une production très rapide puisque stockée préalablement au contraire des molécules devant être synthétisées (IL6,IL1…) 14.

Un phénomène similaire pourrait également être à l’œuvre en cas de réduction, dans le Covid-19, des capacités d’élimination/neutralisation physiologiquement en place au sein de l’organisme. L’un n’excluant pas l’autre, une synergie dans l’origine des effets délétères de l’histamine pourrait ainsi être à l’œuvre (au final : augmentation de ses concentrations extracellulaires et/ou de son temps de présence dans le milieu extracellulaire).

De plus, cette action de l’histamine sur la production d’IL6 ne semblerait pas spécifique à un type de cellules mais a été mis en évidence pour différentes catégories cellulaires (macrophages pulmonaires, monocytes, fibroblastes nasaux)25,26.

Il est à noter que, pour certains types cellulaires (macrophages pulmonaires entre autres), la relation entre production d’IL6 et l’histamine se ferait au travers notamment de son activité sur les RH1 27,28.

Dans la prise en charge du Covid-19, certains espoirs thérapeutiques ont été placés dans un inhibiteur monoclonal de l’IL6 le tocilizumab 30,31 avec des résultats relativement encourageants quant au potentiel thérapeutique 32 .

Dès lors, il apparaît que limiter, en amont, la surproduction d’IL6 puisse ainsi être une voie complémentaire (voire suppressive) à son ciblage électif par le tocilizumab. Les antihistaminiques pourraient avoir un intérêt tout particulier pour se faire. Si l’utilisation des antihistaminiques est tardive, ne permettant ainsi pas d’éviter la surproduction d’IL6, le concept de « thérapie multi-classes à déploiement séquentiel » prend alors tout son sens (déploiement de classes thérapeutiques différentes car actives à des temps différents).

Il apparaît ici que, compte tenu de ce qui a été précédemment mentionné, (expression des RH1, implication des cellules endothéliales dans la synthèse d’IL6 en réponse dose dépendante à l’histamine, sélectivité des antiH1), il soit possible d’envisager plus logiquement une action médiée par des antihistaminiques antiH1. Ceci demeurant à démontrer.

Il n’en demeure pas moins qu’une action complémentaire et cumulative des antihistaminiques puisse être envisagée. En effet, l’activation par l’histamine des récepteurs RH2 étant connue impliquée dans la plus grande efficience d’expression du gène de l’IL6 induit par l’IL125.

Ainsi, la production d’IL1 par les mastocytes engendre une action de potentialisation de la production d’IL6.

Cette dernière notion, très théorique nous permet cependant de mieux appréhender l’intérêt thérapeutique qu’a pu susciter (un temps du moins), l’anakinra (inhibiteur compétitif de l’IL1 à son récepteur de type 1 (IL-1RI)) 33 dans la prise en charge du Covid-19.

Au-delà de cela, la mise en jeu de l’IL1 semble pouvoir en partie relever d’un potentiel inductif de l’histamine quant à, in fine, la libération de cette cytokine. En, effet, de la même manière que l’histamine est « reliable » à une augmentation de la production d’IL6 (et donc participe en tout état de cause au moins à l’augmentation des taux d’IL6), elle pourrait participer à l’augmentation des taux d’IL1, au travers ses effets RH2 34.

Cette mise en jeu, par l’histamine, de différentes cytokines (IL1, IL6) dont les observations et espoirs des contre-mesures thérapeutiques (respectivement anakinra, tocilizumab) largement médiatisées en France dans leur repositionnement dans le cadre de la prise en charge du Covid-19, ne peut qu’inciter (que conforter) l’étude des substances connues actives sur les effets histaminiques directs (en amont de son activation des différents récepteurs cellulaires) ou indirects (ou d’aval, en liens avec les processus liés à l’activation des récepteurs à l’histamine),et particulièrement les molécules d’utilisation sécuritaire telles que les antihistaminiques.

Ainsi, toutes les substances participant à la baisse du taux d’histamine et/ou à la réduction des effets de l’histamine nous apparaissent à prendre en considération dans la lutte contre le Covid-19, et, bien évidemment, en premier lieu les antihistaminiques et autres molécules diminuant la production d’histamine et/ou ses effets.

A ce titre, et à ce stade de notre exposé, il est intéressant de souligner qu’un nombre conséquent de molécules ont été avancées comme potentiellement efficaces et intéressantes dans la réponse thérapeutique à déployer face au Covid-19.

Comme nous venons de le voir, certaines interviendraient en aval de la libération d’histamine (anakinra, tocilizumab). C’est le cas également d’autres substances pour lesquelles des travaux préliminaires ou hypoyhèses fonctionnelles ont évoqué un intérêt (plus ou moins confirmé) dans le Codvid-19 : vitamine D35,36, Quercétine36,37,38, Luteolin39, Carnosine40 notamment.

Ces substances sont connues comme ayant une capacité stabilisatrice sur les mastocytes, participant de facto à la réduction de leur activation et donc à la diminution de la libération d’histamine, mettant en cela, un possible frein (voire arrêt) à la cascade d’événements qui aboutit à la réponse inflammatoire inappropriée observée dans le Covid-19 (à noter que certaines sont connues comme pouvant interagir avec les récepteurs à l’histamine)41,42,43,44.

Notons que, s’agissant, comme indiqué dans l’hypothèse initiale, d’une susceptibilité extrêmement variable (hyperréactivité ou non) en lien avec le système immuno-inflammatoire propre à chacun, l’impact clinique de ce type de molécules peut revêtir une grande variabilité.

Quoiqu’il en soit, le ciblage à un temps donné, d’un effecteur donné de cette cascade répond à la définition d’une thérapie multi-classe à déploiement séquentiel avec en initiateur et « amplificateur » possible les antihistaminiques.

Il est cependant évident que, plus le temps passe et plus l’emballement de la cascade immuno-inflammatoire et les lésions qu’elle induit, relèvent à terme d’une mise en jeu thérapeutique multiple de l’ensemble des acteurs supposés actifs. Les lésions tissulaires micro puis macroscopiques, induites par les phénomènes immuno-inflammatoires, prenant ensuite un rôle pathologique qui leur est propre et dont les contre-mesures thérapeutiques deviennent ensuite spécifiques (voire inexistantes).

C’est la raison pour laquelle, la mise en route des premières contremesures thérapeutiques se doit d’être la plus précoce possible.

Les antihistaminiques, dont la simplicité d’utilisation, le coût modeste et l’effet bloqueur potentiel sont ainsi des candidats des plus prometteurs se devant de bénéficier d’essais cliniques (antiH1 notamment mais également peut-être combinaison antiH1-antiH2).

La séquence d’activation des phénomènes physiopathologiques induits par le SRAS-Cov2, semble bien pouvoir répondre à une cascade d’événements durant laquelle l’histamine intervient à la fois à la phase initiale mais également en participant (sans doute de façon dose dépendante) à la production de cytokines qui, in fine, agiront en elles-mêmes.

Il apparaît donc des plus utile d’envisager le rôle de l’histamine et ce dès la phase initiale d’induction des phénomènes immuno-inflammatoires. L’intérêt des antihistaminiques (en particulier antiH1) prend ainsi son plein sens.

Toute baisse de la sécrétion ou des effets induits par l’histamine, est logiquement d’une importance notable dans la réduction, voire l’arrêt, de la cascade immuno-inflammatoire et ses effets délétères à courts, moyens et longs termes dans le Covid-19.

Ainsi, de façon générale, toute baisse des concentrations extracellulaires d’histamine ou/et tout blocage de son effet diminue ses actions cellulaires, biochimiques et leurs conséquences.

SARS-Cov2/Covi-19 – antihistamines : hypotheses quant aux potentiels, modélisation et étude in vitro

Modélisation – effets in vitro

Différents travaux de modélisation (type binding moléculaire…) ont souligné l’intérêt des antihistaminiques à différents niveau dans le Covid-19 notamment dans leur potentiel d’action anti-virale directe.

Ainsi, l’intérêt du repositionnement d’antihistaminiques était évoqué dans un article paru dans la revue Nature dès avril 202045.

Depuis, différents travaux de modélisation ont permis d’affiner l’intérêt des antihistaminiques. Nous les mentionnerons de façon succincte en schématisant leurs apports.

Clemastine, azelastine et trimeprazine, antagonistes de l’histamine, possèderaient une capacité à s’opposer à l’entrée du virus SARS-Cov2 dans les modèles cellulaires46.

Loratadine et desloratadine, antihistaminiques RH1, possèderaient une capacité à s’opposer à l’entrée du virus SARS-Cov2 dans les modèles cellulaires en bloquant sa liaison avec les récepteurs ACE47.

Famotidine et Cimetidine, antihistaminiques RH2 montreraient une capacité à se fixer sur le SARS-Cov2 et ainsi, comporteraient un intérêt potentiel dans la lutte contre le Covid48.

La doxepine, molécule ayant une activité antiRH1 forte pourrait s’opposer à l’infection des cellules hôtes par le SARS-Cov2 en venant empêcher la fixation de la protéine Spike du virus sur le récepteur ACE2 cellulaire49.

Le Ketotifen, antihistaminique antiH1 serait en capacité de réduire la réplication virale sur modèle cellulaire avec un effet additif ou synergique lorsqu’on y associe certaines autres molécules (naproxene, indomethacine)50.

Chlorpheniramine (antiH1) réduirait de façon très notable la charge virale du modèle, ce qui pourrait laisser supposer un fort pouvoir virucide51.

Hydroxyzine et l’azelastine auraient la capacité de bloquer l’interaction spike-ACE252.

Antihistaminiques et intérêt d’utilisation dans le Covid-19

Un certain nombre d’auteurs ont avancé au travers de différents mécanismes d’action l’intérêt potentiel de divers antihistaminiques dans le Covid-19, nous en ferons ici état de façon schématique.

L’ébastine ainsi que l’Idelalisib molécule dont le potentiel anti-allergique est connu selon les auteurs (rhinite allergique) présenteraient un intérêt dans la prise en charge du Covid-19 53.

La Rupatadine, antihistaminique antiH1, est proposée dans la prévention des microthromboses observées dans le Covid en raison à la fois de son action stabilisatrice sur les cellules mastocytaires et son activité anti PAF (Platelet Activating Factor)54.

L’usage des antihistaminiques en raison de leur action constatée mais aussi de leur sécurité et facilité d’emploi apparaît une hypothèse à promouvoir dans le cadre du repositionnement d’anciennes molécules55.

Un travail de synthèse de la littérature a permis de mettre en avant l’intérêt potentiel des antihistaminiques (RH2) dans le Covid 56.

Dans une revue de la littérature effectuée sur les articles publiés au 27/10/2020 (42 articles) parue en février 2021, PEDDAPALLI et al ont permis de consolider l’importance de l’histamine dans les processus physiopathologiques du Covid. Il a été ainsi mieux appréhendé le potentiel important dans la lutte contre le Covid des molécules limitant les effets de l’histamine ou neutralisant même l’histamine57. L’histamine jouerait ainsi donc un rôle majeur dans les processus lésionnels observés dans le Covid.

De même, un travail tout récent, publié le 26/05/2021, juste avant la fin de rédaction de notre mise à jour, permet de consolider le rôle primordial joué par le système histaminique et les antihistaminiques dans la stratégie de réponse face au Covid-19 58.

D’autres ont avancé sur des bases soit observationnelles soit théoriques en lien avec l’effet de stabilisation connu des antihistaminiques, l’intérêt de cette classe thérapeutique dans la prise en charge du Covid-19.

Ainsi, il a été constaté qu’en Europe, une faible proportion des patients avec troubles psychiatriques était affectée par le SARS- Cov2 59.

Les médicaments psychotropes ont également été ciblés comme potentiellement intéressant dans la prise en charge du Covid-19 60.

Il est intéressant de noter que sur l’ensemble des thérapeutiques potentiellement impliquées chez ce groupe particulier de patients, la quasi-totalité des molécules potentiellement impliquées ont une activité antihistaminique exclusive ou partielle connue (Phénothiazine, chlorpromazine, prométhazine, thiethylperazine, triflupromazine, cyamémazine, levopromazine, propericiazine, pipotiazine, metopimazine, lopéramide, mequitazine, tiotixene, flupentixol, zuclopenthixol, pomozide, haloperidol, astemizole, pipamperone, clomipramine, maitriptyline, benztropine, paroxetine,)

Pour rappel, de nombreux travaux mettent l’accent sur les stabilisateurs des mastocytes, cellules dont le lien direct et indirect avec l’histamine n’est plus à démontrer.

SARS-Cov2/Covid-19 – antihistaminiques : observations, études cliniques et pratique de terrain

Aspects épidémiologiques

A la question de savoir si dans cette pandémie, l’utilisation d’antihistaminiques pourrait apparaitre comme « protectrice », certaines données épidémiologiques ont permis depuis 16 mois, débaucher certains éléments de réponse.

Une petite série pédiatrique italienne faisait état que l’allergie et l’asthme contrôlé apparaissaient possiblement « statistiquement » protecteur face au Covid-19 61.

Aux USA, une étude sur un panel de plus de 219.000 personnes a permis de mettre en évidence une diminution de l’incidence de la positivité au SARS-Cov2 52 corrélée à la prise d’antihistaminique.

De même, en Espagne, une étude rétrospective sur 79.000 personnes aurait permis d’avancer un rôle protecteur possible de la prise d’antihistaminique62.

La prise chronique d’antihistaminique ne semble cependant pas pouvoir empêcher la contamination par le SARS-Cov2 et le développement du Covid-19, et ce en raison même de l’indication de cette médication chronique.

En effet, il semblerait exister une balance entre « niveau » d’histamine et « maladie ». En fait, la prise chronique d’antihistaminique est liée à la maladie « allergie » qui correspond (déjà) à un niveau « élevé » (ou facilement élevable) d’histamine. Dès lors, l’absence de symptôme est liée à la compensation par l’antihistaminique de ce niveau d’histamine élevé ou réactif.

Ainsi, il existe (ou non) une capacité « résiduelle » de compensation, un « réservoir » d’effet antihistaminique plus ou moins important selon chacun. Le Covid augmentant (pour schématiser) l’histamine, si cette capacité résiduelle permet de compenser il pourrait dans notre hypothèse, ne pas y avoir développement du Covid-19 sinon il faut en théorie (et dans nos constats cliniques), soit augmenter la dose soit changer la molécule.

A ce titre (type de molécule) certains antihistaminiques pourraient avoir plus de capacité à inhiber l’infestation par le SARS-Cov2 mais, rappelons que la charge virale pourrait ne pas être, pour certains, le seul élément impactant le déclenchement de la maladie Covid-19. Il s’avère alors que, même si certains antihistaminiques s’avéraient in vivo protecteurs, il pourrait y avoir débordement de cette capacité protectrice face à la charge virale importante ou la sensibilité/réactivité individuelle.

Autrement dit, les allergiques « chroniques » traités par antihistaminiques ont un équilibre entre processus allergique spontané (et plus ou moins permanent) et efficacité du traitement antihistaminique. Ils ne développent donc pas de symptômes, grâce à cet équilibre. Après contage, le SARS-Cov2 engendrerait selon notre hypothèse première, une libération d’histamine, point de départ de la cascade immuno-inflammatoire (« théorie du couloir »). Ainsi, bien que sous antihistaminique, certains patients allergiques chroniques traités verraient leur quantité d’histamine dépasser celle des bloqueurs HRH1 et la cascade immuno-inflammatoire débuterait (avec une puissance plus ou moins grande selon la « marge de manœuvre antihistaminique » disponible).

Ainsi, pour prendre en charge ces malades il faut soit augmenter la dose d’antiH1 soit changer d’antiH1 (soit l’associer à un antiH2).

Études cliniques

Depuis février 2020, des études cliniques sont venues en confirmation du constat fait dans nos travaux observationnels.

Il a été ainsi démontré l’intérêt potentiel de certains antihistaminiques RH2 dans la prise en charge du Covid-19. La famotidine aurait ainsi montré une capacité à réduire le nombre d’intubations et de décès chez les patients hospitalisés63.

L’utilisation d’antihistaminiques antiH1 et antiH2 a montré un intérêt dans le Covid64.

L’utilisation d’antihistaminique et d’azithromycine a montré sa capacité d’améliorer de façon notable le pronostic des patients atteints de Covid65. Une prise en prophylaxie des antihistaminiques au niveau des sujets contacts semblerait montrer également une efficacité notable.

A noter que récemment, une équipe sud-africaine a fait état de ses résultats qui semblent plus qu’encourageant dans la prise en charge du Covid-19 au moyen d’antihistaminiques (non publié).

Malgré l’importance primordiale que nous semble représenter le système histaminique dans le Covid-19, à ce jour, peu d’études cliniques ont été réalisées.

Les réticences, incompréhensibles, face aux repositionnements d’anciennes molécules dans le schéma thérapeutique déployable dans le Covid semblent en être peut-être la cause. Cela ne concerne bien évidement pas que les antihistaminiques, mais ces derniers semblent largement ignorés dans leur potentiel…ignorance stratégique, méconnaissance de leur potentiel ou total inintérêt dans le Covid, le temps jugera.

SARS-Cov2/Covi-19 – antihistaminiques : activité non RH dépendante, liens et activité antihistaminique-like d’autres classes thérapeutique

L’activité des antihistaminiques pourrait également être médiée par une action non récepteur dépendant.

Ainsi, certains antihistaminiques antiH1 possèderaient une action anti-inflammatoire au travers de certaines interactions sur la production des prostaglandines 2 (PG2), sans que cette activité ne soit dévolue qu’à leur seule activité RH166.

Soulignons que l’histamine présente également une dualité d’effet sur l’inflammation avec une capacité pro ou anti-inflammatoire selon le type cellulaire et le type de récepteur considéré. L’histamine serait ainsi impliquée dans une inhibition de la synthèse des leucotriènes (LT) avec réduction de l’action de la 5-lipopoxygénase 67. Cet effet, médié par les récepteurs antiH2, est antagonisé par la ramitidine (antiH2) qui induit une suppression plus ou moins complète de la réduction de biosynthèse des LT 67.

Ainsi, les actions des antiH2 pourraient induire une augmentation relative de la production de LT et, avec elle, réduire le potentiel actif des antiH2 sur une part de l’immuno-inlammation.

Les antiH1 ne semblent pas se heurter à cette effet suppresseur ou diminuant de l’action anti-inflammatoire parfois observée. Dès lors, et de façon purement théorique, il pourrait en résulter une action soit moins rapide, soit partielle des antiH2 par rapport aux antiH1.

Nous pouvons dès lors entrevoir également l’intérêt potentiel des anti leucotriènes au travers de leur positionnement, évoqué dans l’hypothèse initiale, au sein des contre-mesures anti-inflammatoires possibles et ce, indépendamment de leur action possible et associée sur l’adhésion virale68. L’action des anti leucotriènes peut par ailleurs également être complétée par leur capacité connue à baisser la production, entre autres de l’IL6 69 dont nous avons abordé le très probable implication dans le Covid-19.

Ces données, se doivent bien évidement d’être approfondies. Les notions d’éventuelles affinités partielles et activations croisées prenant ici toute leur importance de même que celle de la dualité fonctionnelle de l’histamine.

Ces possibilités d’action « croisée » et de dualité fonctionnelle de l’histamine viennent complexifier encore les actions connues des différents récepteurs spécifiques de l’histamine. Le concept de rétrocontrôle et d’effets interdépendant est également à considérer, à l’instar de ce qui peut être observé au niveau neuronal entre RH3 et RH1 70. De même, les expressions cellulaires variables (y compris sur le plan temporel) des récepteurs ainsi que les effets de co activations (par exemple RH1 et RH4) est également possiblement source d’actions différentiées71.

Au-delà des relations complexes de l’histamine avec ses différents récepteurs spécifiques -RH 1 à 4-, cette amine biogène est également connue pour entrer en relation avec d’autres récepteurs et notamment des récepteurs aux cytokines.

S’ouvrent ainsi, les actions possibles sur les réponses immuno-inflammatoires en lien avec, peut-être, lymphocytes T helper CD4*, lymphocytes T CD8* et NK72 dont l’implication dans la réponse infectieuse est évidement à considérer. Les interactions des amines biogènes (et particulièrement de l’histamine), sur les récepteurs cytokiniques impliqués notamment dans la réponse antivirale, ont du reste été appréhendées73, ouvrant ainsi un champ complexe de recherches quant à la compréhension des mécanismes à l’œuvre et des balances d’action ou de différenciation induites.

Entre action hors récepteurs dédiés, activation, modulation et autres rétrocontrôles, la compréhension des mécanismes à l’œuvre offre un vaste champ de réflexion et d’exploration.

A cette complexité d’action du système antihistaminique lui-même, l’apport de molécules impactant les voies d’aval de l’activation primordiale histaminique, complexifie encore les choses dans l’émergence d’un traitement de référence.

Par exemple, le rôle que semble jouer la vitamine D dont l’importance en qualité de cofacteur de la lutte antimicrobienne est connue74 : Partant de l’implication antimicrobienne possible et de données épidémiologiques, la possible utilité de la vitamine D a été mise en avant dans la prise en charge du Covid-19 75.

Une supplémentation est ainsi, parfois conseillée afin d’optimiser la lutte antimicrobienne y compris pour le SARS-Cov2 76.

Cela suffira à l’Académie Française de Médecine pour recommander via un communiqué en date du 22 mai 2020 d’apporter une supplémentation systématique en vitamine D en cas de Covid-1977 et ce, même si l’effet bénéfique d’une supplémentation des cas sévères de Covid-19 n’aurait cependant pas démontré d’efficacité tangible78 .

Ce faisant, la vitamine D participerait au maintien de la stabilité des mastocytes et son déficit serait associé à leur activation79.

Une supplémentation apporterait ainsi, en cas de déficit, une aide stabilisatrice rendant moins effective la mise en jeu de l’histamine au décours du Covid-19, cela nous semble cependant marginal mais, comme indiqué toute limitation de la libération d’histamine nous apparaît utile.

Cette notion de classe thérapeutique différente de celle des antihistaminiques mais ayant une activité qui, au final converge en partie sur le système histaminique est importante à aborder.

Il est en effet à considérer les actions « antihistaminique-like » de certaines molécules ou classes thérapeutiques.

Ainsi, certains antidépresseurs sembleraient être prometteurs dans leur potentiel de lutte contre le Covid-19. Une étude observationnelle rétrospective multicentrique menée en France en partenariat AP-HP et INSERM a montré une diminution du risque d’intubation et de décès chez les malades atteints de Covid et bénéficiant d’un traitement par certains antidépresseurs (fluoxétine, paroxétine, escitalopram, venlaflaxine et mirtazapine).

Il s’avère intéressant de souligner ici que ces cinq antidépresseurs ont tous une action antihistaminique connue.

De même, dès avril 2020, certaines études semblaient montrer une diminution de la prévalence du Covid chez les fumeurs amenant à s’interroger sur le rôle protecteur possible de la nicotine. Soulignons que ces études n’abordaient que l’aspect de prévalence et non la gravité liée au tabagisme en cas de Covid81,82.

Là encore, un lien avec les voies histaminiques existe puisque certaines études tendent à montrer que la nicotine semblerait en capacité de provoquer une diminution de la production d’histamine, au niveau cellulaire et tissulaire83,84.

Nous pouvons également évoquer la chloroquine et l’hydroxychloroquine dont la médiatisation rend inutile l’exposé du possible potentiel dans le Covid. Il existe en effet là encore un lien connu entre ces molécules et le système histaminique soit « d’aval » (activation des mastocytes)85,86 soit plus directement lié à l’histamine87.

On remarquera qu’il existe une dualité dans l’effet sur le système histaminique de la chloroquine avec, possible réduction de sa libération par effet stabilisateur des mastocytes et effet de diminution de l’élimination de l’histamine par possible effet inhibiteur sur l’histamine N-methyl transferase.

Pour rappel, il existe une dualité d’avis et constats dans le Covid sur l’effet de la cholorquine. En phase précoce, elle semblerait utile alors qu’en phase plus avancée certains la décrive délétère. Dès lors, nous pouvons avancer que la phase précoce ne correspond pas encore à une activation « pleine » des mastocytes, l’effet stabilisateur sera donc pleinement bénéfique tandis qu’en phase tardive, l’activation mastocytaire est « lancée » avec une augmentation de facto de la libération d’histamine et la baisse de la dégradation de l’histamine n’apparaît pas très pertinente.

Encore une fois, la complexité des mécanismes à l’œuvre et l’emballement du système immuno-inflammatoire plaident pour une prise en charge la plus précoce possible.

Quoiqu’il en soit un lien existe bien entre voie histaminique et chloroquine.

Dans le registre des convergences d’actions biologiques, l’ivermectine fait actuellement partie des molécules dont l’activité dans le Covid semble prometteuse, nous ne reviendrons pas sur les multiples travaux ayant rapporté son efficacité dans la prise en charge du Covid, au regard de la polémique créée actuellement pour n’en mentionner qu’une, celle de P. KORY 88 pour laquelle nous avons un regard tout particulier en lien avec une récente polémique mettant l’accent sur les difficultés actuelles en termes de communication scientifique89. Il est en effet intéressant de signaler que les avermectines possèdent, chez les invertébrés, une action sur le système histaminique selon diverses études in vitro.

Il serait donc intéressant d’affiner les éventuelles liaisons, en biologie humaine, avermectine et système histaminique90,91.

Par ailleurs, soulignons que les avermectines sont structurellement proches des macrolides (sans posséder d’action antibiotique). Ceci ouvre un champ intéressant de recherche notamment de mimétisme moléculaire, quant aux constats d’actions bénéfiques possibles de certains antibiotiques de cette famille.

Cette notion de mimétisme moléculaire, très théorique revêt cependant un attrait tout particulier à bien considérer. Par exemple, le Molnupiravir, présenté dans la presse grand public comme la potentielle « pilule anti-Covid » est la prodrogue de l’hydroxycytidine92. L’hydroxycytidine a été étudiée quant à ces cibles moléculaires possibles notamment en se basant sur des molécules voisines (conformation moléculaire)93. L’azacytidine et l’adénosine sont deux des trois molécules structurellement comparables. Hors, l’azacytidine est connue pour avoir une affinité avec les methyltransferase et l’adénosine est quant à elle connue pour avoir une action inhibitrice de la libération d’histamine par les cellules mastocytaires pulmonaires (avec à plus forte concentration et après pénétration intracellulaire (donc plus tard), un effet inverse)94.

Ici encore, la relation reste très théorique et demande bien évidement à être affinée mais il existe indubitablement un axe de recherche pertinent dans le cadre de possibles mimétismes moléculaires.

Nous avons précédemment mentionné le constat par certaines équipes de l’intérêt de l’antibiothérapie (azithromycine notamment) dans le Covid et ce, au-delà des éventuelles surinfections bactériennes associées.

Cela amène à s’interroger, outre l’hypothétique mimétisme moléculaire, sur les mécanismes possibles d’action des antibiotiques dans cette pathologie.

Il a été avancé que le microbiote digestif semble impliqué dans la sévérité du Covid, probablement en lien avec son impact sur la réponse immune de l’hôte. Il pourrait également être impliqué dans la persistance à long terme de symptômes du Covid95.

Un lien notable, à mieux appréhender bien évidement, pourrait être le fait que certaines bactéries notamment à tropisme intestinal, sont connues comme ayant la capacité de sécréter de l’histamine96.

SARS-Cov2/Covi-19 – facteurs de risque et antihistaminiques

Mentionnons enfin quelques pistes de liens possibles soulignant l’intrication probable des différents éléments impliqués sur le plan métabolique lors de l’atteinte par le SARS-Cov2.

Le diabète a été identifié comme étant un facteur de risque de gravité dans le Covid. Là encore, la relation entre taux de glucose et système histaminique semble devoir être appréhendé plus avant en raison des liens connus entre taux de glucose et histamine97,98.

A ce titre, il faut remarquer que l’obésité, autre facteur de risque connu dans le Covid, au-delà des troubles de ventilation qui peuvent lui être imputés, comporte certes une fréquente association avec un trouble de régulation glycémique mais également, un lien avec le système histaminique, et ce au-delà d’une action centrale médiée par les RH3 puisque, la graisse abdominale pourrait être source de dysproduction d’histamine.

De même, à l’instar de ce qui a pu être observé au niveau cérébral lors du développement99, il serait intéressant d’évaluer production d’histamine, sensibilité à l’histamine et âge.

Au total

Il nous apparaît licite de considérer les antihistaminiques antiH1 comme une stratégie thérapeutique à envisager dans le Covid-19.

Les observations entrent pleinement dans les attendus de la théorisation initialement présentée de même que bon nombre de données récentes issues des progrès des connaissances et de cibles thérapeutiques émergentes possibles.

Certains résultats nous confortent cependant dans la notion d’un déploiement (ou combinaison) thérapeutique séquentiel qui serait un élément pouvant optimiser la prise en charge du Covid-19, suivant en cela les cascades du système immuno-inflammatoire.

A chaque phase, certaines contre-mesures thérapeutiques ciblées : antihistaminiques, anti leucotriènes, antipaludéens de synthèse, corticoïdes et autres médicaments s’opposant aux phénomènes immuno-inflammatoires. Leur utilisation devant être adaptée à la phase immuno-inflammatoire la plus « bruyante ».

Il s’agit donc d’une prise en charge avec une sorte de « thérapie multi classe à déploiement séquentiel » selon le stade évolutif biochimique le plus intensément à l’œuvre au moment de la prise en charge du malade, faisant de facto du traitement du Covid-19 un traitement à adaptation individuelle mais pour lequel l’histamine semble être le fil conducteur basal.

Quoiqu’il en soit, l’enjeu premier est bien le blocage au plus précoce de la contamination par le SARS-Cov2 des effets délétères induit par l’interaction hôte-agent pathogène.

L’efficacité des antihistaminiques antiH1 au cours du Covid-19 se doit d’être mieux appréhendée. Leur potentiel d’utilité dans le Covid-19 semblant pouvoir être mis à profit dans la phase aigüe mais également envisager dans les possibles complications à long terme, qui pourraient découler d’une mise en jeu (parfois infra clinique) du système immuno-inflammatoire (fibrose pulmonaire…).

De même, les formes à évolution prolongée doivent faire envisager la persistance d’une activation anormale (et à bas bruit) du système immuno-inflammatoire ou des réinfections sans immunisation stable. Les effets délétères à long terme demeurent également chez ses patients, au-delà d’un enjeu de santé individuelle, un enjeu en termes de santé publique. Il convient d’explorer plus avant les composantes de ces formes prolongées.

L’évolution des connaissances sur la relation entre SARS-Cov2, Covid-19 et histamine ne viennent que conforter l’utilité et, l’urgence de réaliser des études complémentaires de validation clinique.

Conflit d’intérêt : aucun

Contact auteur : CetiCov1@protonmail.com

1 Spécialiste en médecine générale, DiuEA Maladies Systémiques et Polyarthrites, dip fac Médecine de Grenoble, France

Assisté (données observationnelles, veille actualités médicales (apport nu non intégré), contacts et diffusion) par :

Docteur Sophie GONNET (2),

Docteur Edith KAJI (3),

Docteur Hélène REZEAU-FRANTZ (4)

2 Médecine générale, Capacité en médecine d’urgence et médecine de catastrophe, dip fac Médecine de Nice, France

3 Médecine générale, Capacité gériatrie, dip fac Médecine de Pavie/Dijon, Italie / France

4 Médecine générale, médecine générale, dip fac Médecine de Paris, France

REMERCIEMENTS

Monsieur Bruno CASSANI pour son aide dans la veille bibliographique (apports nus non intégrés) et sa traduction anglaise,

Monsieur Franck GUERIN pour son aide dans la veille bibliographique (apports nus non intégrés) et son soutien,

Etude observationnelle initiale : mars-avril 2020

Mise à jour : 05/06/2020 - 02/06/2021

REFERENCES

1. Arminjon S, Gonnet S, Kaji E, Rezeau-Frantz H Effets des antihistaminiques dans la prise en charge thérapeutique du Covid-19, à propos de 26 patients, available on https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Annwyne-Houldsworth-2/post/Are-Angiotensin-Receptor-Blocker-Trials-as-Therapy-Inhibiting-COVID-19-Infection-Successful/attachment/5eb02081c005cf0001882c60/AS%3A887470908530693%401588600961846/download/Antihistamines+as+a+therapeutic+care+plan+of+Covid-19+About+26+cases+%281%29.pdf

2. Article R.4127- 8 du code de la santé publique de la République Française :

3. Borriello F, Iannone R, Marone G. Histamine Release from Mast Cells and Basophils. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;241:121‐139. doi:10.1007/164_2017_18

4. Branco ACCC, Yoshikawa FSY, Pietrobon AJ, Sato MN. Role of Histamine in Modulating the Immune Response and Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018 Aug 27;2018:9524075. doi: 10.1155/2018/9524075. PMID: 30224900; PMCID: PMC6129797.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30224900/

5. Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer LL. Cytokine signaling--regulation of the immune response in normal and critically ill states. Crit Care Med. 2000 Apr;28(4 Suppl):N3-12. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004001-00002. PMID: 10807312.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10807312/

6. Ananthanarayan,R ;Paniker,C.K.J. A text book of Microbiology, Orient Longman limited 1992 ISBN0-86311-194-7

7. Folkerts G, Verheyen AK, Geuens GM, Folkerts HF, Nijkamp FP. Virus-induced changes in airway responsiveness, morphology, and histamine levels in guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(6 Pt 1):1569‐1577. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1569 (REF Cochon) https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1569

8. Cheng H, Lear-Rooney CM, Johansen L, Varhegyi E, Chen ZW, Olinger GG, Rong L. 2015. Inhibition of Ebola and Marburg virus entry by G protein-coupled receptor antagonists. J Virol 89:9932–9938. doi:10.1128/JVI.01337-15.

9. Xu Wei, Xia Shuai, Pu Jing, Wang Qian, Li Peiyu, Lu Lu,

Jiang Shibo, The Antihistamine Drugs Carbinoxamine Maleate and

Chlorpheniramine Maleate Exhibit Potent Antiviral Activity Against a

Broad Spectrum of Influenza Viruses

Frontiers in Microbiology VOLUME9,2018, p2643

https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02643

DOI=10.3389/fmicb.2018.02643, ISSN=1664-302X

10. Y Li, L Chi, DJ Stechschulte,KN Dileepan, La production induite par l’histamine d’interleukine 6 et d’interleukine 8 par les cellules endothéliales de l'artère coronaire humaine est améliorée par l’endotoxine et le facteur de nécrose tumorale-Alpha MICROVASC RES.2001 mai ; 61 (3) :253-62.

11. Masini E, Di Bello MG, Raspanti S, et al. The role of histamine in platelet aggregation by physiological and immunological stimuli [published correction appears in Inflamm Res. 2013 Feb;62(2):249. Fomusi Ndisang, J [corrected to Ndisang, J F]]. Inflamm Res. 1998;47(5):211‐220. doi:10.1007/s000110050319

12. Schunack W. What are the differences between the H2-receptor antagonists?. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1987;1 Suppl 1:493S‐503S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.1987.tb00658.x

13. Demopoulos C, Antonopoulou S, Theoharides TC. COVID-19, microthromboses, inflammation, and platelet activating factor. Biofactors. 2020 Nov;46(6):927-933. doi: 10.1002/biof.1696. Epub 2020 Dec 9. PMID: 33296106.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33296106/

14. Kritas SK, Ronconi G, Caraffa A, Gallenga CE, Ross R, Conti P.

Mast cells contribute to coronavirus-induced inflammation: new

anti-inflammatory strategy [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb

4]. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents.

2020;34(1):10.23812/20-Editorial-Kritas.

doi:10.23812/20-Editorial-Kritas

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32013309

15. Kilinc E, Baranoglu Y. Mast cell stabilizers as a supportive therapy can contribute to alleviate fatal inflammatory responses and severity of pulmonary complications in COVID-19 infection. Anatol Clin Tıp Bilim Derg. 2020;25 111–8. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/anadoluklin/issue/53241/720116

16. Raymond M, Ching-A-Sue G, Van Hecke O, Mast cell stabilisers, leukotriene antagonists and antihistamines : A rapid review of effectiveness in COVID-19, website CEBM university of Oxford, https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/mast-cell-stabilisers-leukotriene-antagonists-and-antihistamines-a-rapid-review-of-effectiveness-in-covid-19/

17. CONTI P et al in Journal of biological regulators and homeostatic agents vol 34 n°5 1629-1632(2020)

18. Robert W. Malone, Philip Tisdall, Philip Fremont-Smith, Yongfeng Liu, Xi-Ping Huang, Kris M. White, Lisa Miorin, Elena Moreno Del Olmo, Assaf Alon, Elise Delaforge, Christopher D. Hennecker, Guanyu Wang, Joshua Pottel, Robert Bona, Nora Smith, Julie M. Hall, Gideon Shapiro, Howard Clark, Anthony Mittermaier, Andrew C. Kruse, Adolfo García-Sastre, Bryan L. Roth, Jill Glasspool-Malone, Victor Francone, Norbert Hertzog, Maurice Fremont-Smith, Darrell O. Ricke COVID-19 : Famotidine, Histamine, Mast Cells and Mechanisms

Prepublication https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-30934/v1

19. Theoharides TC. Potential association of mast cells with coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021 Mar;126(3):217-218. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.11.003. Epub 2020 Nov 6. PMID: 33161155; PMCID: PMC7644430.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33161155/

20. Peddapalli A, Gehani M, Kalle AM, Peddapalli SR, Peter AE, Sharad S. Demystifying Excess Immune Response in COVID-19 to Reposition an Orphan Drug for Down-Regulation of NF-κB: A Systematic Review. Viruses. 2021 Feb 27;13(3):378. doi: 10.3390/v13030378. PMID: 33673529; PMCID: PMC7997247.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33673529/

21. Afrin LB, Weinstock LB, Molderings GJ. Covid-19 hyperinflammation and post-Covid-19 illness may be rooted in mast cell activation syndrome. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Nov;100:327-332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.016. Epub 2020 Sep 10. PMID: 32920235; PMCID: PMC7529115.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32920235/

22. Varga et al ; Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19 : The Lancet vol 395 may 2020,

23. Linares DM, del Rio B, Redruello B, et al. Comparative analysis of the in vitro cytotoxicity of the dietary biogenic amines tyramine and histamine. Food Chem. 2016;197(Pt A):658‐663. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.11.013

24. Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 15]. Transl Res. 2020;S1931-5244(20)30070-0. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

25. Vannier E, Dinarello CA. Histamine enhances interleukin (IL)-1-induced IL-6 gene expression and protein synthesis via H2 receptors in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(13):9952‐9956.

26. Delneste Y, Lassalle P, Jeannin P, Joseph M, Tonnel AB, Gosset P. Histamine induces IL-6 production by human endothelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98(2):344‐349. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06148.x

27. Park IH, Um JY, Cho JS, Lee SH, Lee SH, Lee HM. Histamine Promotes the Release of Interleukin-6 via the H1R/p38 and NF-κB Pathways in Nasal Fibroblasts. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014;6(6):567‐572. doi:10.4168/aair.2014.6.6.567

28. Triggiani M, Gentile M, Secondo A, et al. Histamine induces exocytosis and IL-6 production from human lung macrophages through interaction with H1 receptors. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):4083‐4091. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4083 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11238657/?from_single_result=Histamine+Induces+Exocytosis+and+IL-6+Production+from+Human+Lung+Macrophages+Through+Interaction+with+H1+Receptors

29. Takizawa H, Ohtoshi T, Kikutani T, et al. Histamine activates bronchial epithelial cells to release inflammatory cytokines in vitro. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;108(3):260‐267. doi:10.1159/000237162

30. Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, Zhao H, Wang GQ. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(5):105954. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954

31. Fu B, Xu X, Wei H. Why tocilizumab could be an effective treatment for severe COVID-19?. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):164. Published 2020 Apr 14. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02339-3 (

32. Luo P, Liu Y, Qiu L, Liu X, Liu D, Li J. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19: A single center experience [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 6]. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25801. doi:10.1002/jmv.25801

33. https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2020/20200428147918/anx_147918_fr.pdf

34. Vannier E, Dinarello CA. Histamine enhances interleukin (IL)-1-induced IL-1 gene expression and protein synthesis via H2 receptors in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Comparison with IL-1 receptor antagonist. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(1):281‐287. doi:10.1172/JCI116562

35. Houldsworth A (2021) The Perfect Storm: Review: Immune Dysregulation in Severe COVID-19 and the Possible Role of Mast CellVitamin D Interactions. J Emerg Dis Virol 6(1): dx.doi.org/10.16966/2473-1846.161

https://www.sciforschenonline.org/journals/virology/JEDV161.php

36. Glinsky GV. Tripartite Combination of Candidate Pandemic

Mitigation Agents: Vitamin D, Quercetin, and Estradiol Manifest

Properties of Medicinal Agents for Targeted Mitigation of the COVID-19

Pandemic Defined by Genomics-Guided Tracing of SARS-CoV-2 Targets in

Human Cells. Biomedicines. 2020 May 21;8(5):129. doi:

10.3390/biomedicines8050129. PMID: 32455629; PMCID: PMC7277789.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32455629/

37. Derosa G, Maffioli P, D'Angelo A, Di Pierro F. A role for

quercetin in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Phytother Res. 2021

Mar;35(3):1230-1236. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6887. Epub 2020 Oct 9. PMID:

33034398; PMCID: PMC7675685.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33034398/

38. Colunga Biancatelli RML, Berrill M, Catravas JD, Marik PE.

Quercetin and Vitamin C: An Experimental, Synergistic Therapy for the

Prevention and Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Related Disease (COVID-19). Front

Immunol. 2020 Jun 19;11:1451. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01451. PMID:

32636851; PMCID: PMC7318306.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32636851/

39. Theoharides TC. COVID-19, pulmonary mast cells, cytokine

storms, and beneficial actions of luteolin. Biofactors. 2020

May;46(3):306-308. doi: 10.1002/biof.1633. Epub 2020 Apr 27. PMID:

32339387; PMCID: PMC7267424.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7267424/

40. Jindal C, Kumar S, Sharma S, Choi YM, Efird JT. The Prevention

and Management of COVID-19: Seeking a Practical and Timely Solution.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jun 4;17(11):3986. doi:

10.3390/ijerph17113986. PMID: 32512826; PMCID: PMC7312104.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32512826/

41. Kimata M, Shichijo M, Miura T, Serizawa I, Inagaki N, Nagai H.

Effects of luteolin, quercetin and baicalein on immunoglobulin

E-mediated mediator release from human cultured mast cells. Clin Exp

Allergy. 2000 Apr;30(4):501-8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00768.x.

PMID: 10718847.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10718847/

42. Yang CC, Hung YL, Li HJ, Lin YF, Wang SJ, Chang DC, Pu CM,

Hung CF. Quercetin inhibits histamine-induced calcium influx in human

keratinocyte via histamine H4 receptors. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021 Apr

13;96:107620. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107620. Epub ahead of print.

PMID: 33862555.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33862555/

43. Weng Z, Zhang B, Asadi S, Sismanopoulos N, Butcher A, Fu X,

Katsarou-Katsari A, Antoniou C, Theoharides TC. Quercetin is more

effective than cromolyn in blocking human mast cell cytokine release and

inhibits contact dermatitis and photosensitivity in humans. PLoS One.

2012;7(3):e33805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033805. Epub 2012 Mar 28.

PMID: 22470478; PMCID: PMC3314669.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22470478/

44. Mlcek J, Jurikova T, Skrovankova S, Sochor J. Quercetin and Its Anti-Allergic Immune Response. Molecules. 2016 May 12;21(5):623. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050623. PMID: 27187333; PMCID: PMC6273625.

45. Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, Xu J, Obernier K, White KM,

O'Meara MJ, Rezelj VV, Guo JZ, Swaney DL, Tummino TA, Hüttenhain R,

Kaake RM, Richards AL, Tutuncuoglu B, Foussard H, Batra J, Haas K, Modak

M, Kim M, Haas P, Polacco BJ, Braberg H, Fabius JM, Eckhardt M,

Soucheray M, Bennett MJ, Cakir M, McGregor MJ, Li Q, Meyer B, Roesch F,

Vallet T, Mac Kain A, Miorin L, Moreno E, Naing ZZC, Zhou Y, Peng S, Shi

Y, Zhang Z, Shen W, Kirby IT, Melnyk JE, Chorba JS, Lou K, Dai SA,

Barrio-Hernandez I, Memon D, Hernandez-Armenta C, Lyu J, Mathy CJP,

Perica T, Pilla KB, Ganesan SJ, Saltzberg DJ, Rakesh R, Liu X, Rosenthal

SB, Calviello L, Venkataramanan S, Liboy-Lugo J, Lin Y, Huang XP, Liu

Y, Wankowicz SA, Bohn M, Safari M, Ugur FS, Koh C, Savar NS, Tran QD,

Shengjuler D, Fletcher SJ, O'Neal MC, Cai Y, Chang JCJ, Broadhurst DJ,

Klippsten S, Sharp PP, Wenzell NA, Kuzuoglu-Ozturk D, Wang HY, Trenker

R, Young JM, Cavero DA, Hiatt J, Roth TL, Rathore U, Subramanian A,

Noack J, Hubert M, Stroud RM, Frankel AD, Rosenberg OS, Verba KA, Agard

DA, Ott M, Emerman M, Jura N, von Zastrow M, Verdin E, Ashworth A,

Schwartz O, d'Enfert C, Mukherjee S, Jacobson M, Malik HS, Fujimori DG,

Ideker T, Craik CS, Floor SN, Fraser JS, Gross JD, Sali A, Roth BL,

Ruggero D, Taunton J, Kortemme T, Beltrao P, Vignuzzi M, García-Sastre

A, Shokat KM, Shoichet BK, Krogan NJ. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction

map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020

Jul;583(7816):459-468. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. Epub 2020 Apr 30.

PMID: 32353859; PMCID: PMC7431030.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32353859/

46. Yang, L., Pei, Rj., Li, H. et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitors among already approved drugs. Acta Pharmacol Sin (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-020-00556-6

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41401-020-00556-6

47. Hou Y, Ge S, Li X, Wang C, He H, He L. Testing of the

inhibitory effects of loratadine and desloratadine on SARS-CoV-2 spike

pseudotyped virus viropexis. Chem Biol Interact. 2021 Apr 1;338:109420.

doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109420. Epub 2021 Feb 18. PMID: 33609497; PMCID:

PMC7889471.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33609497/

48. Ishola AA, Joshi T, Abdulai SI, Tijjani H, Pundir H, Chandra

S. Molecular basis for the repurposing of histamine H2-receptor

antagonist to treat COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021 Jan 25:1-18.

doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1873191. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33491579;

PMCID: PMC7852284.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33491579/

49. Shuai Ge, Xiangjun Wang, Yajing Hou, Yuexin Lv, Cheng Wang,

Huaizhen He,Repositioning of histamine H1 receptor antagonist: Doxepin

inhibits viropexis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike pseudovirus by blocking ACE2,

European Journal of Pharmacology,Volume 896,2021,173897,ISSN 0014-2999, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173897.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/coronavirus/publication/33497607

50. Kiani P, Scholey A, Dahl TA, McMann L, Iversen JM, Verster JC.

In Vitro Assessment of the Antiviral Activity of Ketotifen,

Indomethacin and Naproxen, Alone and in Combination, against SARS-CoV-2.

Viruses. 2021 Mar 26;13(4):558. doi: 10.3390/v13040558. PMID: 33810356;

PMCID: PMC8065848.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33810356/

51. Westover JB, Ferrer G, Vazquez H, Bethencourt-Mirabal A, Go

CC. In Vitro Virucidal Effect of Intranasally Delivered Chlorpheniramine

Maleate Compound Against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

2. Cureus. 2020 Sep 17;12(9):e10501. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10501. PMID:

32963923; PMCID: PMC7500730.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32963923/

52. Reznikov LR, Norris MH, Vashisht R, Bluhm AP, Li D, Liao YJ,

Brown A, Butte AJ, Ostrov DA. Identification of antiviral antihistamines

for COVID-19 repurposing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021 Jan

29;538:173-179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.11.095. Epub 2020 Dec 3. PMID:

33309272; PMCID: PMC7713548.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7713548/

53. Palma G, Pasqua T, Silvestri G, Rocca C, Gualtieri P, Barbieri

A, De Bartolo A, De Lorenzo A, Angelone T, Avolio E, Botti G. PI3Kδ

Inhibition as a Potential Therapeutic Target in COVID-19. Front Immunol.

2020 Aug 21;11:2094. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02094. PMID: 32973818;

PMCID: PMC7472874.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32973818/

54. Demopoulos C, Antonopoulou S, Theoharides TC. COVID-19,

microthromboses, inflammation, and platelet activating factor.

Biofactors. 2020 Nov;46(6):927-933. doi: 10.1002/biof.1696. Epub 2020

Dec 9. PMID: 33296106.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33296106/

55. Gitahy Falcao Faria C, Weiner L, Petrignet J, Hingray C, Ruiz

De Pellon Santamaria Á, Villoutreix BO, Beaune P, Leboyer M, Javelot H.

Antihistamine and cationic amphiphilic drugs, old molecules as new tools

against the COVID-19? Med Hypotheses. 2021 Mar;148:110508. doi:

10.1016/j.mehy.2021.110508. Epub 2021 Jan 24. PMID: 33571758; PMCID:

PMC7830196.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33571758/

56. Ennis M, Tiligada K. Histamine receptors and COVID-19. Inflamm

Res. 2021 Jan;70(1):67-75. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01422-1. Epub 2020

Nov 18. PMID: 33206207; PMCID: PMC7673069.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33206207/

57. Peddapalli A, Gehani M, Kalle AM, Peddapalli SR, Peter AE,

Sharad S. Demystifying Excess Immune Response in COVID-19 to Reposition

an Orphan Drug for Down-Regulation of NF-κB: A Systematic Review.

Viruses. 2021 Feb 27;13(3):378. doi: 10.3390/v13030378. PMID: 33673529;

PMCID: PMC7997247.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33673529/

58. Qu C, Fuhler GM, Pan Y. Could Histamine H1 Receptor

Antagonists Be Used for Treating COVID-19? Int J Mol Sci. 2021 May

26;22(11):5672. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115672. PMID: 34073529.

https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/22/11/5672

59. Javelot H, Petrignet J, Addiego F, Briet J, Solis M, El-Hage

W, Hingray C, Weiner L. Towards a pharmacochemical hypothesis of the

prophylaxis of SARS-CoV-2 by psychoactive substances. Med Hypotheses.

2020 Nov;144:110025. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110025. Epub 2020 Jun 23.

PMID: 33254478; PMCID: PMC7309834.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33254478/

60. Villoutreix BO, Beaune PH, Tamouza R, Krishnamoorthy R,

Leboyer M. Prevention of COVID-19 by drug repurposing: rationale from

drugs prescribed for mental disorders. Drug Discov Today. 2020

Aug;25(8):1287-1290. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.06.022. Epub 2020 Jun

25. PMID: 32593662; PMCID: PMC7315962.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32593662/#affiliation-1

61. Ciprandi G, Licari A, Filippelli G, Tosca MA, Marseglia GL.

Children and adolescents with allergy and/or asthma seem to be protected

from coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020

Sep;125(3):361-362. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.06.001. PMID: 32859351;

PMCID: PMC7447212.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7447212/

62. Vila-Córcoles A, Ochoa-Gondar O, Satué-Gracia EM, et al Influence

of prior comorbidities and chronic medications use on the risk of

COVID-19 in adults: a population-based cohort study in Tarragona, Spain

BMJ Open 2020;10:e041577. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041577

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7733229/

63. Freedberg DE, Conigliaro J, Wang TC, Tracey KJ, Callahan MV,

Abrams JA; Famotidine Research Group. Famotidine Use Is Associated With

Improved Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A

Propensity Score Matched Retrospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology.

2020 Sep;159(3):1129-1131.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.053. Epub

2020 May 22. PMID: 32446698; PMCID: PMC7242191.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32446698/

64. Hogan Ii RB, Hogan Iii RB, Cannon T, Rappai M, Studdard J,

Paul D, Dooley TP. Dual-histamine receptor blockade with cetirizine -

famotidine reduces pulmonary symptoms in COVID-19 patients. Pulm

Pharmacol Ther. 2020 Aug;63:101942. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2020.101942.

Epub 2020 Aug 29. PMID: 32871242; PMCID: PMC7455799.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32871242/

65. Morán Blanco JI, Alvarenga Bonilla JA, Homma S, Suzuki K,

Fremont-Smith P, Villar Gómez de Las Heras K. Antihistamines and

azithromycin as a treatment for COVID-19 on primary health care - A

retrospective observational study in elderly patients. Pulm Pharmacol

Ther. 2021 Apr;67:101989. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2021.101989. Epub 2021 Jan

16. PMID: 33465426; PMCID: PMC7833340.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33465426/

66. Roch-Arveiller M, Tissot M, Idohou N, Sarfati G, Giroud JP, Raichvarg D. In vitro effect of cetirizine on PGE2 release by rat peritoneal macrophages and human monocytes. Agents Actions. 1994;43(1-2):13‐16. doi:10.1007/BF02005756

67. Flamand N, Plante H, Picard S, Laviolette M, Borgeat P. Histamine-induced inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis in human neutrophils: involvement of the H2 receptor and cAMP. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141(4):552‐561. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0705654

68. Fidan C, Aydoğdu A. As a potential treatment of COVID-19: Montelukast [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 11]. Med Hypotheses. 2020;142:109828. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109828